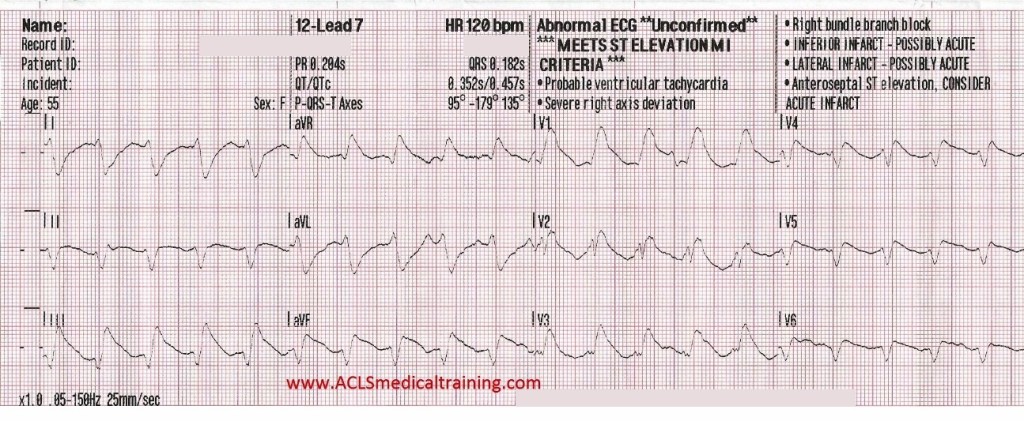

Wide Complex Tachycardia Treated With Amiodarone and Synchronized Cardioversion

A 55 year old male presents to EMS with complaint of intermittent shortness of breath.

Symptom onset occurred while he was taking his daily walk about 15 minutes prior to EMS arrival.

The patient has a Glasgow Coma Score of 15, with a patent airway, clear lung sounds, and mild respiratory distress. Strong and regular bilateral radial pulses are noted, with no obvious signs of hypoperfusion.

The following medical history is reported:

- Hypertension

- Coronary artery disease

- 2 coronary stents of unknown location

- Occasional smoking and alcohol consumption

Medications include metoprolol, nitroglycerin tablets, and daily supplements.

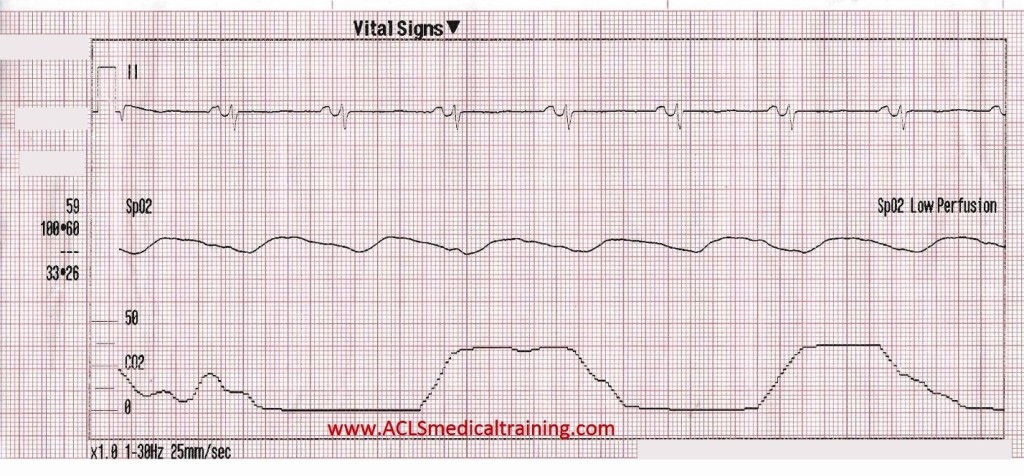

Vital signs are assessed.

- RR: 25

- HR: 62

- NIBP: 141/91

- SpO2: 99% on room air

- BGL: 97 mg/dL

The patient is placed on the cardiac monitor.

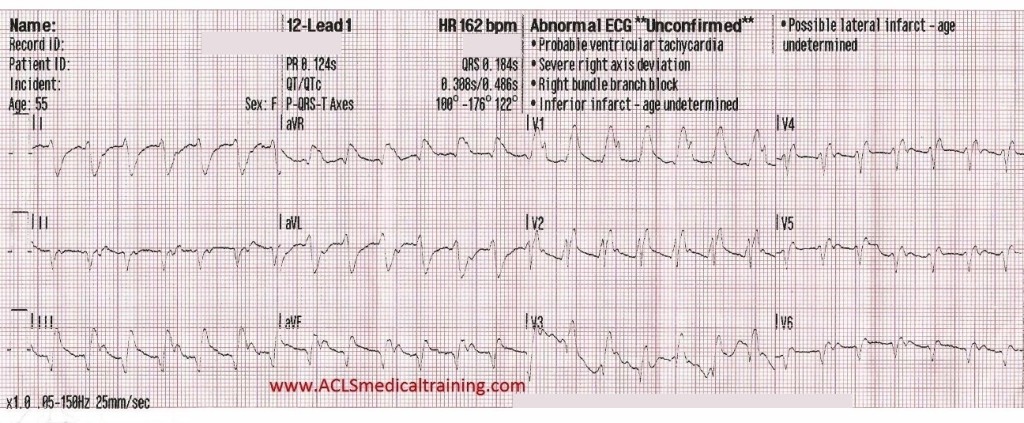

A few seconds later the patient complains of acute shortness of breath, while the initial 12 lead ECG is obtained.

The following questions come to mind:

- What is the rhythm?

- Could this be the cause of the sudden onset of shortness of breath?

- Is the patient stable or unstable?

- What will your treatment consist of?

We should note that there is a regular Wide Complex Tachycardia (WCT) which should be presumed to be Ventricular Tachycardia (VT) until proven otherwise. You may or may not have time to fully scrutinize the ECG depending on the patient status.

A regular WCT should be presumed as VT until proven otherwise!

One important reason this should be our train of thought is that VT is less likely to be tolerated by a patient with a cardiac history or structural heart disease compared to a younger individual without these mitigating factors.

Three main possible causes of WCT should be considered:

- VT

- SVT with aberrancy (i.e. reentry tachycardia with a Bundle Branch Block)

- Antidromic AVRT (requires an accessory pathway)

There are multiple criteria to differentiate VT from SVT with aberrancy. The two conditions can be difficult to distinguish and in some cases, impossible.

Findings considered supportive of VT:

- Structural heart disease or previous myocardial infarction

- An extremely wide QRS complex > 160 ms (0.16s)

- The presence of AV dissociation

- The presence of fusion and captured beats

- QRS concordance in the precordial leads (i.e., all negative or all positive)

- Extreme Right Axis Deviation (ERAD)

- However, the absence of ERAD does not rule out VT

- Wellens, Brugada, or Verekei’s Criteria (outside the scope of this case study)

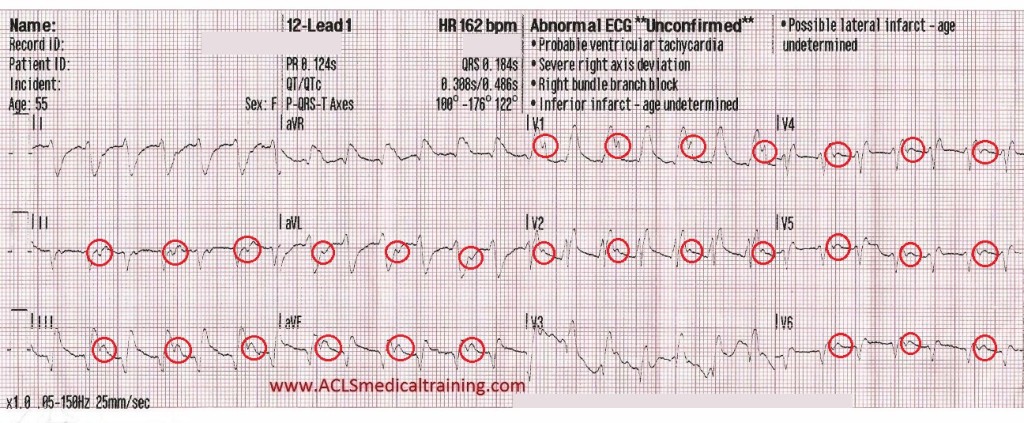

Let’s take a look at the same ECG again with some highlighted points.

- There is a very broad QRS of at least 180 ms (0.18s)

- Extreme right axis deviation is noted at -176 degrees

- Ventricular complexes outnumber atrial complexes by a 2:1 ratio (marked with red circles)

- There is a monophasic R wave in lead V1

All of these findings support the diagnosis of ventricular tachycardia, but again, VT should be your default diagnosis!

Oxygen was given via nasal cannula @ 3 LPM, IV access was established, defibrillation pads were placed, and 150 mg amiodarone drip was started.

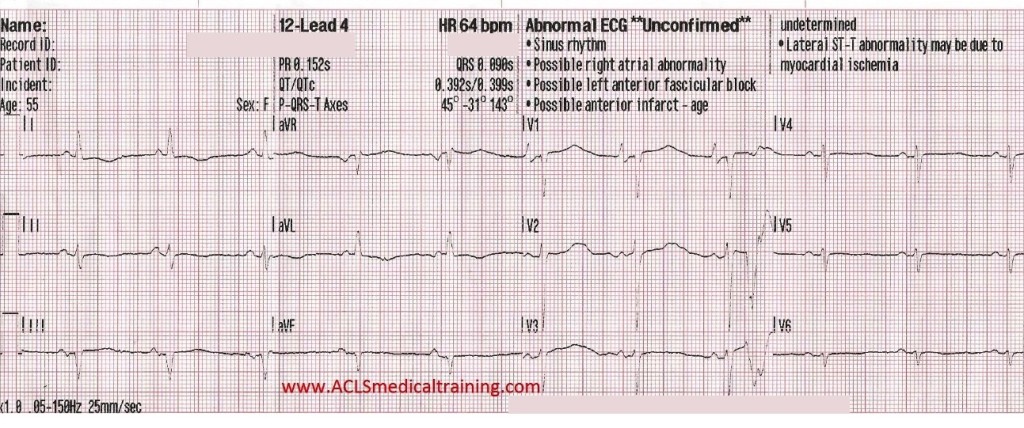

A few seconds after starting the amiodarone drip the patient reported relief of shortness of breath and the following 12-lead ECG was recorded.

Approximately 4 minutes later the shortness of breath returned along with substernal chest pressure.

The presence of one or more of the following qualifies a patient as unstable.

- Hypotension

- Ischemic chest pain

- Dyspnea

- Pulmonary edema

- Altered mental status

The patient was given 2 mg of midazolam and synchronized cardioversion was performed @ 100 J which converted the patient back to sinus rhythm. The amiodarone drip was completed and the patient’s symptoms were completely resolved by arrival in the emergency department.

Discussion

Consider this recommendation from the 2010 AHA ECC Guidelines (unchanged in 2015):

“For patients who are stable with likely VT, IV antiarrhythmic drugs or elective cardioversion is the preferred treatment strategy. If IV antiarrhythmics are administered, procainamide (Class IIa, LOE B), amiodarone (Class IIb, LOE B), or sotalol (Class IIb, LOE B) can be considered. Procainamide and sotalol should be avoided in patients with prolonged QT. If one of these antiarrhythmic agents is given, a second agent should not be given without expert consultation (Class III, LOE B). If antiarrhythmic therapy is unsuccessful, cardioversion or expert consultation should be considered (Class IIa, LOE C).”

Although procainamide, lidocaine and sotalol are proven to be effective and even preferred by some clinicians, amiodarone (Class III antiarrhythmic with potassium, calcium, and sodium channel blocking properties) remains the primary antiarrhythmic agent in the prehospital setting for wide complex tachycardia.

Adenosine can be used initially for stable regular wide complex tachycardia. This is because a WCT caused by SVT with aberrancy (and right ventricular outflow tract ventricular tachycardia) are responsive to adenosine.

Synchronized Cardioversion is the preferred treatment for unstable WCT.

Conclusion

- Wide complex tachycardia should be treated as ventricular tachycardia until proven otherwise

- Stable WCT can be addressed with antiarrhythmic agents or synchronized cardioversion

- Administration of multiple antiarrhythmic agents should be avoided without expert consultation

- Treatment of unstable WCT should be synchronized cardioversion

- Synchronized cardioversion is acceptable and avoids some of the pitfalls of antiarrhythmic infusion

Reference

Neumar R, Otto C, Link M et al. Part 8: Adult Advanced Cardiovascular Life Support: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation. 2010;122(18_suppl_3):S729-S767. doi:10.1161/circulationaha.110.970988.

Comments