PlatooStock // Shutterstock

CPR can double or triple a person’s chance of survival—here’s how it was developed

If you go into cardiac arrest outside of a hospital in the United States, your chances of surviving are not good: Some 70%–90% of people who experience out-of-hospital cardiac arrest die before reaching a hospital, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The American Heart Association reports that, on average, someone dies as a result of cardiovascular disease every 36 seconds in the United States, or 2,380 people a day. As for strokes, someone dies every three minutes and 33 seconds, on average—about 405 deaths caused by stroke each day.

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation, or CPR, can change those numbers. If performed immediately, CPR can double or even triple your chances of surviving a cardiac arrest in your home (where 70% occur), out in public, or in a nursing home. The use of an automated external defibrillator, which delivers a shock through your chest to your heart, can also improve your odds of living. Attempts to resurrect victims of heart attacks, drownings, or other emergencies have a long history. Early references can be found in Egyptian mythology and the biblical Book of Kings, as well as in modern times, when CPR, a technique now taught in basic life support training, was developed in the 1930s.

Citing academic journals and news reports, ACLS Medical Training, a continuing education provider for advanced cardiac life support training, compiled a timeline of the history of CPR. Click through to learn more about this life-saving technique.

hemro // Shutterstock

Before the 19th century: Varying methods from flagellation to bellows precede modern CPR

Our earliest written history traces basic attempts to resurrect someone who has just stopped breathing. References can be traced back to Egyptian mythology, as when Isis resurrected Osiris with “the breath of life,” for example. In the Book of Kings in the Old Testament, there is a description of the prophet Elisha saving a boy in part by placing his mouth over the boy’s mouth.

In 1530, Swiss physician Paracelsus may have tried using a bellows on a dead patient. The founder of modern anatomy, Andreas Vesalius, another 16th-century physician, also described making a hole in an animal’s trachea and blowing to inflate its lung, whereas Scottish surgeon William Tossach reported reviving a coal miner who had been felled by gasses.

Maria Wan // Shutterstock

1868: First accounts of sternal compression recorded

A 21st-century surgeon said an 1868 account of sternal compression by a doctor at the Royal Free Hospital in London “could equally be a present-day description of external cardiac massage.” The article in the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, titled “Modern cardiopulmonary resuscitation—not so new after all,” noted that the method described was likely an attempt at artificial respiration rather than heart compression. The patient breathed ammonia from a large sponge during the compression. However, the method was almost identical to what would be discovered almost 100 years later.

By the early 19th century, artificial breathing was overtaken by external compression, which was adopted as the best approach to revive someone after it was deemed dangerous to give someone air from which some oxygen had already been removed.

Racha Phuangpoo // Shutterstock

1933: William Kouwenhoven ‘accidentally’ develops modern CPR technique while researching external defibrillation

Dr. William Kouwenhoven, the founder of modern-day CPR, discovered the technique while he was researching heart defibrillation on a dog. Kouwenhaven realized that rhythmic pressure on the dog’s sternum could bring enough circulation to its brain. The pace needed was 36 kilograms of pressure every second. He reported that adequate circulation could be kept for 30 minutes with external compression. By 1960, he was able to show a 70% survival rate among 20 human patients who had gone into cardiac arrest.

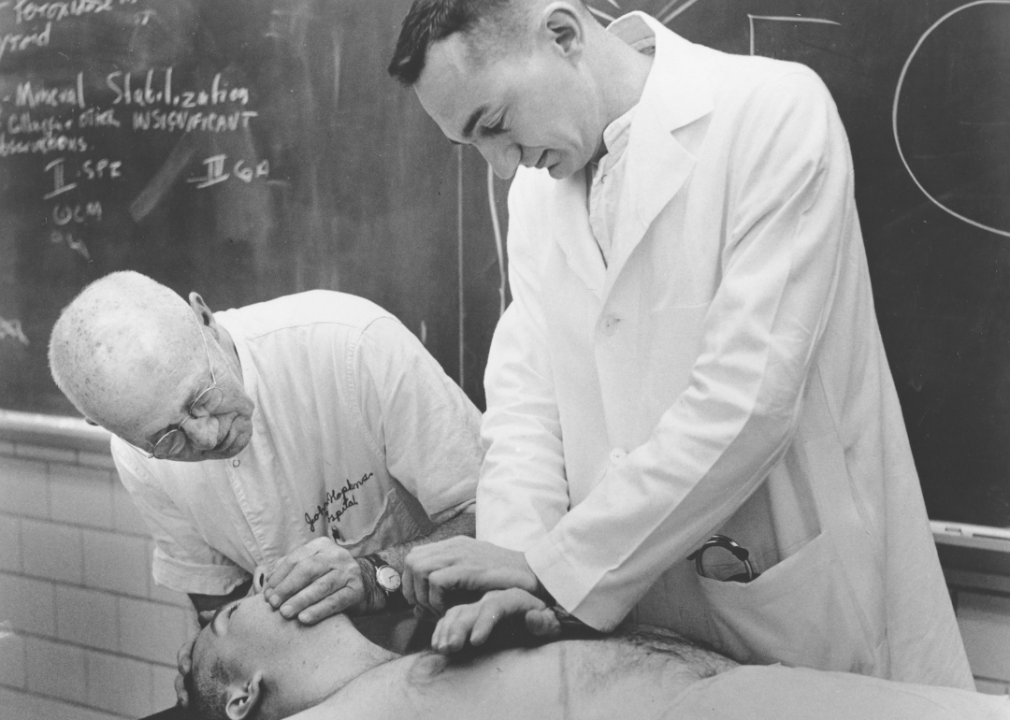

Bettmann // Getty images

1938: Vladimir Negovsky establishes first resuscitation laboratory in Moscow

Russian scientist Dr. Vladimir Negovsky established the first resuscitation lab in Moscow, which is pictured above with a nurse monitoring testing. There, he developed the ideas of terminal state, clinical death, post-resuscitation disease, and what he called reanimatology, the science of resuscitation. He focused on preventing the destruction of the central nervous system and restoring function after clinical death. During World War II, Negovsky created front-line resuscitation teams who were able to resuscitate soldiers. In 1959, his laboratory started mobile resuscitation teams in Moscow.

Ken Wolter // Shutterstock

1949: Red Cross invites CPR pioneers to evaluate techniques

The Red Cross asked a team of doctors including Dr. Archer Gordon to evaluate different methods of chest compression. Gordon, a heart specialist, found that applying pressure on the chest rather than the back was more effective. Gordon demonstrated that mouth-to-mouth resuscitation was better for children by using techniques which had been developed by Dr. Peter Safar, a pioneer in critical care medicine who had studied ways to resuscitate patients.

pixelaway // Shutterstock

1956: Mouth-to-mouth resuscitation deemed an effective method for life-saving techniques

For many years, Dr. Peter Safar studied techniques to resuscitate patients through exhaling into a patient’s airways and his research would eventually show that mouth-to-mouth resuscitation is effective at saving lives. He and Dr. James Elam, who was an expert in the respiratory system and invented many types of ventilators, partnered to pioneer the steps of CPR such as how to lift a patient’s chin and initiate rescue breathing. A year later, the U.S. military adopted mouth-to-mouth resuscitation as a technique to be used for emergency life support.

JHU Sheridan Libraries/Gado // Getty Images

1960: First CPR training mannequin is created

A life-sized training mannequin was designed to teach people how to perform CPR during training courses. The mannequin was a collaboration between Drs. Peter Safar, Archer Gordon, James Elam and Norwegian toymaker Åsmund Lærdal. More than 400 million people around the world have learned CPR skills in training courses, according to the American Heart Association.

The face of the mannequin, named Resusci Annie, was modeled after that of a teenage girl who drowned in Paris, the River Seine, in the late 19th century. Never identified, she became known as “L’Inconnue de la Seine,” the Unknown Woman of the Seine.

Tony Harris – PA Images // Getty Images

1974: Standards for CPR adopted by various medical organizations

The American Red Cross and other organizations asked for training and performance standards for CPR. As a result, the National Academy of Sciences’ research council convened a conference. A second national conference for CPR and Emergency Cardiovascular Care, or ECC, took place in 1973. A year later, the American Red Cross along with the American Medical Association and the American Heart Association adopted “Standards for CPR,” written by Dr. Archer Gordon.

Africa Studio // Shutterstock

2010s: Hands-only CPR gains popularity for bystander use

Hands-only CPR eliminates the need for a bystander to put their mouth in contact with someone they are trying to help. Medical professionals hope that by removing rescue breathing from the technique, more people will come forward to help.

Hands-only CPR can double the survival rate of someone experiencing cardiac arrest. Why does it work? According to the American Heart Association, when a teenager or an adult collapses as a result of cardiac arrest, their lungs and blood have enough oxygen for their vital organs as long as someone is doing chest compressions to pump blood to their heart and brain.

David P. Smith // Shutterstock

2021: Five states pass laws requiring 911 dispatchers be trained in instructing CPR over the phone

Dispatchers able to provide instructions in CPR can increase the likelihood that a bystander will perform CPR, therefore raising the rate of survival from cardiac arrest. A 2009 study in the journal Circulation noted that in many communities bystanders performed CPR on fewer than a quarter of those suffering from cardiac arrest before emergency medical services arrived.

In 2021, legislators in five states—Indiana, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, Texas, and Virginia—passed laws requiring 911 dispatchers to learn to instruct CPR over the phone. The practice dates to 1974, when a 911 call was received seeking help for a child who was drowning. A medic was able to help the caller keep the child alive until an emergency medical services team arrived.